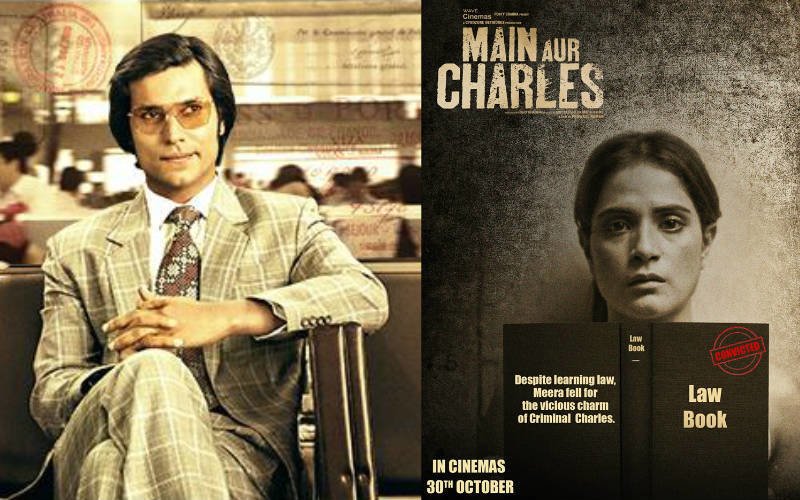

Main Aur Charles Is All Psychedelics, Less Psyche

The film glosses over the serial killer's monstrosities without making any attempt at truly understanding his complex persona

In his book, The Life And Crimes Of Charles Sobhraj, Australian writer Richard Neville, the famous chronicler of the counterculture wave of the sixties, made an interesting observation about the charismatic criminal. He wrote, "Whatever life he touches, he wrecks. His pattern is to befriend, then drug and rob, or drug and murder, or, while in jail, manipulate and betray."

The description instantly evokes a vivid portrait, of an enigmatic man who nobody could completely understand, who went on to become one of the most notorious criminals ever known. Nicknamed 'Serpent' for his unpredictably manipulative turns, Sobhraj's' magnetism is known to be irresistible, his appeal overpoweringly giddy.

Unfortunately, director Prawaal Raman's film possesses neither of that. What it has is excessive focus on style that eventually makes the film burn in its own desperate zeal to look 'uber cool.' Main Aur Charles is a delight to watch only if you look at the scenes independently without trying to link them. Because they aren't stitched together seamlessly, which one expects from a top-rate feature with a competent editor.

The story begins in Thailand where bodies of bikini-clad women are found offshore. To avoid death penalty, Sobhraj plots his escape to India, but isn't completely done with the crime-bug. He carries that with himself, just like the hairstyle, glares and swag, and infects the hippies with his malicious and shadowy ways. On the trail are cops from three different cities. The narrative is largely built on this cat-and-mouse game jumping timelines between the past and the present.

As Sobhraj, Randeep Hooda appears largely wooden. Originally, Sobhraj is half-Vietnamese and half-French (born to an Indian tailor in Vietnam, raised by a Frenchman who married his mother later) and Hooda's accent in the film is as confusing as the strange combination of these two nationalities. Any minute, it feels that the Highway actor will break into Haryanvi expletives, tired in his attempts to keep the accent consistent. While there is obvious physical resemblance, Hooda doesn't quite make the character as eerie as it's meant to be and always looks as if he's portraying a part, rather than living it. His character is charismatic, but what makes him so? He can bed women in a heartbeat, but what draws them to him? These are questions never addressed, but you are still expected to accept him for the perception the felon has managed to create.

The film never bothers to delve into the reasons why Sobhraj did what he did; neither does it explicitly deal with the gruesome killings he's been convicted for. In fact, it almost feels like a propaganda piece for a ruthless murderer, shining in his own shadowy glory, enjoying the 70-mm fame he always aspired to attain. (Sobhraj, in real life, had ambitious plans of selling his 'life story' for astronomical amounts for print publication and film documentation).

Being in the realm of fiction, the film isn't obliged to condemn him, but it doesn't do a fantastic job of glorifying, or representing him accurately either. Random characters walk in and disappear, the supporting cast is mediocre, the dialogue is archaic and extremely expository while Richa Chadda is plain insufferable. For an actress of her caliber, she appears shockingly amateur, speaks her lines as if auditioning for a part she shouldn't have gotten, while her face remains devoid of any true emotion. In between all of this, random pop-philosophy comes in the form of Hooda's dialogues.

A womaniser, a manipulator, a murderer, a man who fancied himself worldly-wise - quoted Hitler and Nietzsche - and ultimately, a sociopath deserving of urgent medical attention. A portrayal of this kind of complexity requires a lot more flair than some kaleidoscopic camera-work and thumping background score. It demanded an actor above Hooda's skills and a director interested in psyche and not just psychedelics.

While watching the film is not entirely a criminal waste of time, the Sobhraj story could have been turned into something as extraordinary as Steven Spielberg's Catch Me If You Can. A couple of twists in the end could serve as the film's saving grace just like its atmospheric quality does, but that's pretty much all there is to it. No psychological revelation, no true darkness to devour, no better understanding of motives, no clear method to the madness.

This is one exploit Charles Sobhraj wouldn't be much proud of.

Thumbnail Image Source: facebook/MainAurCharles

_2024-12-23-5-53-49_small.jpg)

_2024-12-23-10-10-26_small.jpg)

_2024-12-24-7-11-13_small.jpg)